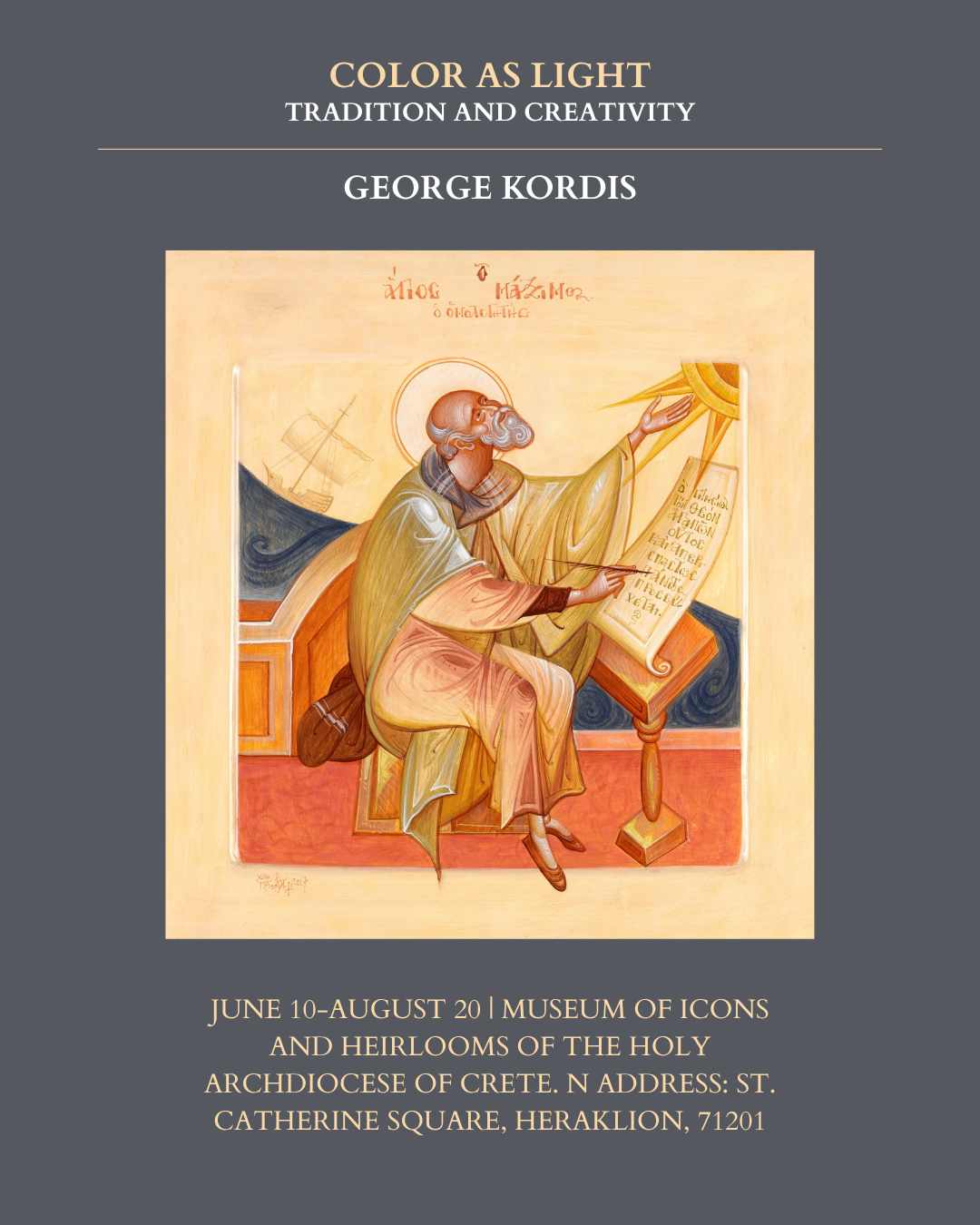

There is much debate, especially among Western European and American iconographers, about which verb best describes creating an image: the verb write or the verb paint.

In Greek and Slavic languages, I think the verb paint has at its base the same root as the verb write. Thus, there is no question or confusion. Whether one says that one paints or writes the pictures is one and the same.

Personally, I have tended in recent years to accept the verb γράφω (write) as more appropriate. This is not for reasons of tradition – for traditionally, the verb γράφω has been used primarily for the act of painting – but for other reasons related to how the composition is composed.

And I explain.

The way the Greek world conceived of painting is far from the modern way that originated in Renaissance painting. According to it, the painting represents apparent reality, the creation through visual artifacts (perspective, naturalism, external light source, and light shading) of a substitute for reality, the creation of a virtual ( false) reality.

Even when it imitates the forms of reality (after the classical era, mainly 5th century BC), the Greek pictorial style is not structurally representational. It does not create a different virtual reality in relation to the recipient of the visual work but builds its composition in the same space-time as the viewers.

The composition is based on geometry, visual rules, and principles based on physics.

More specifically, all the forces of the work are placed on cross axes (often curved and hidden within the structure of the objects), creating rhythmic conduction on the surface.

The exact same structure exists in the letters of the Greek alphabet. All forces and the final structure obey are cross-relationships.

Thus, writing as composition-structure is painting, and painting is writing. Certainly, however, it is not representation.

Later, especially in late antiquity, with the transformations that Greek art has undergone in its contact with the regional cultural entities with which it came into contact with the conquests of Alexander the Great, painting became actual writing. That is the development of visual signs on a surface in terms of writing ( starting from the top left and moving downwards to the right and integrating all relations in cross axes).

Christian iconographic art borrowed its mode of composition from this visual current of “late antiquity expressionism” because this served better its need for narrative while avoiding a virtual reality detached from the congregation, which would raise ecclesiological issues.

For the same reasons, I think it is better to speak of writing to describe the how of the creation of the icons.

The scribe (painter) of the images synthesizes, with a selective abstraction equivalent to poetry, visual data (hypostatic figures of historical persons) with the logic of a text, with the freedom afforded by not adhering to a representational-naturalistic logic to present to the church congregation (viewers) the history primarily of the Divine Economy as a presence and not as a memory of a past event.